White paper on Cultural Diversity in the Workplace

This survey on workplace cultures has been underway for a long time. Gugin Leadership Research Institute does a lot of specialised research for our clients, but that is usually always confidential.

From my 19000 contacts on LinkedIn I selected 6560 people who met the criteria. I also submitted the survey to the professional groups I administer on LinkedIn and Xing. Former colleagues and clients in IBM, Fortis, Novartis, Apple and Shell were very helpful in distributing the survey among their colleagues.

Consequently I don’t know exactly how many people have received an invitation to take the survey, but 1292 people have answered it, and I am going to present the results below.

I have promised the respondents anonymity so I will not disclose results segmented on company.

About Dr Finn Majlergaard

Dr Finn Majlergaard is the managing partner in Gugin – a consulting firm specialised in helping companies around the world benefitting from the cultural diversity You can learn more about Dr Finn Majlergaard and visit his linkedin profile. Feel free to connect with him on LinedIn as well.

I have been working with cross-cultural management for many years and even before I started my own company 15 years ago I knew that most of the challenges I was facing as manager in global operating companies in one way or the other was related to differences in cultures. Differences in workplace cultures and the underlying personal value system often created so much operational friction that it sometimes became impossible to fulfil the goals and objectives.

Then one can ask. If differences in culture are such a huge obstacle for achieving success in global operating companies why don’t we put a lot of resources into finding a solution? After having talked to a lot of clients and attendees on my courses about it I think most people fall in one of two categories.

They either don’t believe in things that do not appear in a spreadsheet or they don’t have the internal organisational power in their company to change the focus to cross-cultural team effectiveness.

So before starting the project of writing a doctoral dissertation on the subject I was keen to find out whether or not the challenges of managing and leading global organisation were real or only existed in the heads of people working in the HR departments.

The workplace survey

I therefore decided to conduct a survey among middle managers in global operating companies around the world. I decided to define a global company as a company who has its presence on at least 3 continents. I also decided only to ask middle managers because they feel the daily dilemma between the different cultures and the dilemma between the corporate culture and the various national and professional cultures.

Lets have a closer look at the answers they gave to the questions:

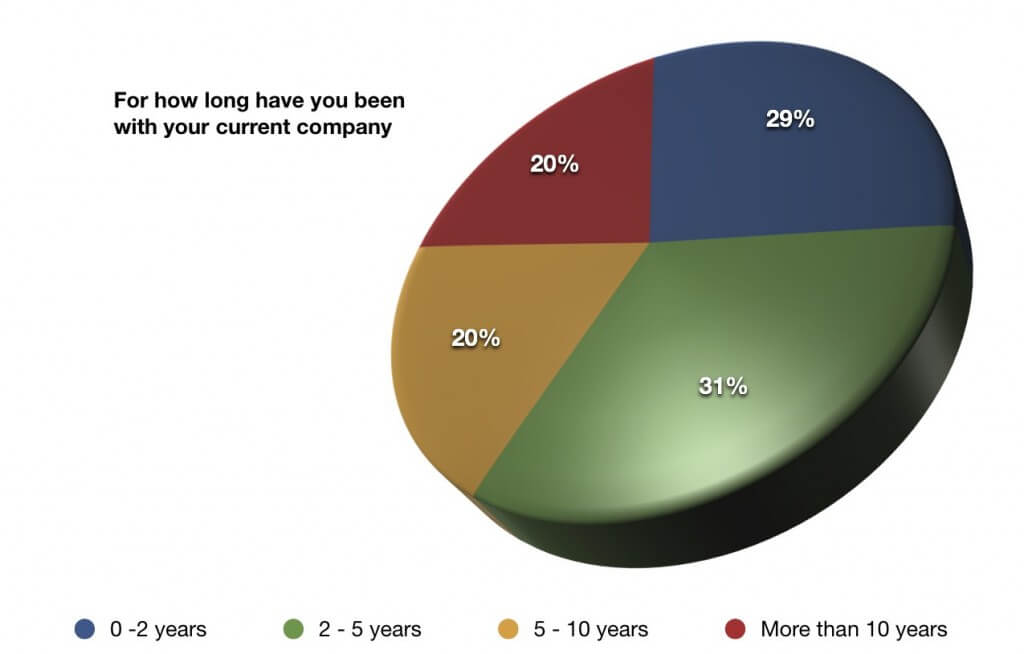

How long have the respondents been with their current company?

As culture, whether its workplace – or national culture is something you understand over time, it was important for me to know for how long the respondents have been working with their current company.

As it shows on the chart above 71% of the respondents have been with their current company for more than 2 years and 40% of them have been with their company for more than 5 years.

Since so many of the respondents have been with their company for several years I think it is fair to conclude that they are more positive about the company’s values and culture than a group of newcomers. Some of the newcomers will always feel disappointed or just don’t fit in and they will most likely leave the company again after a short while.

That argument is important to bear in mind when we examine the other results below.

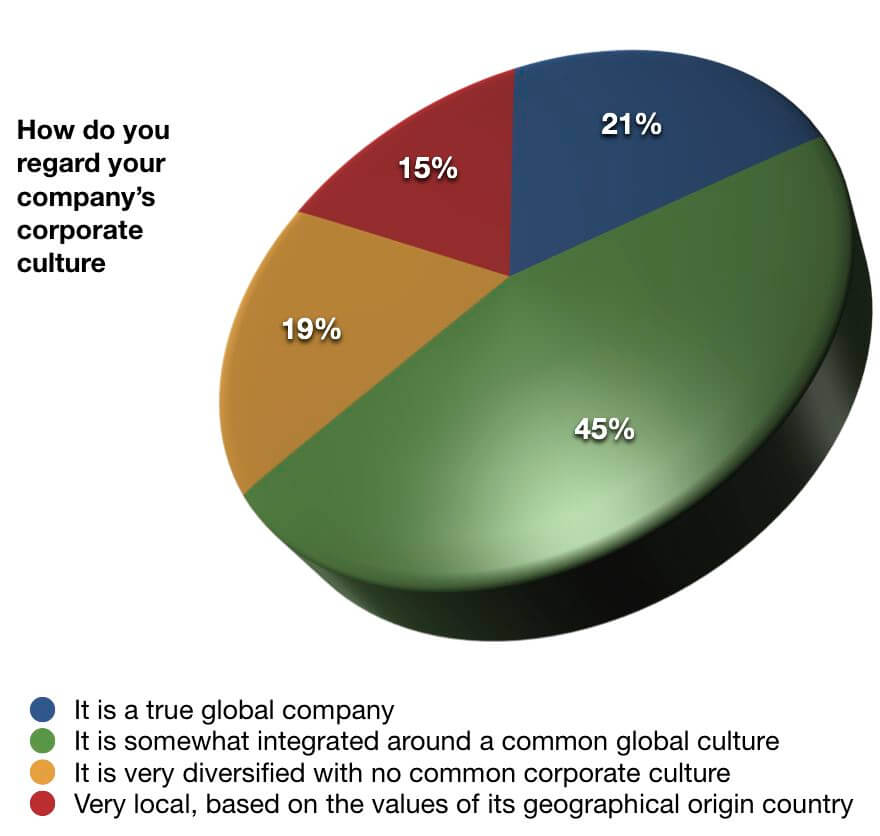

How do you regard your company’s workplace culture?

In my dissertation I focused on which kind of workplace culture a company had and the advantages and disadvantages a model has in relation to achieve operational excellence in a global environment. That is why I asked the respondents about the cultural diversity in the workplace specifically.

Only 21% regard their company as a true global company and almost as many – 19%, think that their company is very diversified with no common corporate culture. The majority of the respondents do however find that their company has a global corporate culture in the range from somewhat integrated to a true global company.

What do I mean by a true global company? Since we are dealing with people’s perceptions and feelings it is impossible to quantify. To me it was most important how people were feeling about their company. If the employees feel it is a true global company, then it is a true global company – attitude determines altitude!

I am not surprised that so many found their company to have a common global culture. Firstly most of the companies participating in this survey have been around for a long time and the majority of the people answering the questionnaire have medium to long seniority with the company where they work. These are both factors contributing to the statistical outcome above.

15% of the respondents find that their company has a culture similar to the one where it is originated and it has developed into a global organisation when it comes to culture. It is a typical for a company who in the beginning was very successful in its home market and then steadily grew into a company with global presence. A number of companies are behaving like that – maybe because the Danish culture is tribal in its construction. In my dissertation I examined the corporate culture of a couple of companies in detail and outlined the concerns I had and determined the key barriers for global success.

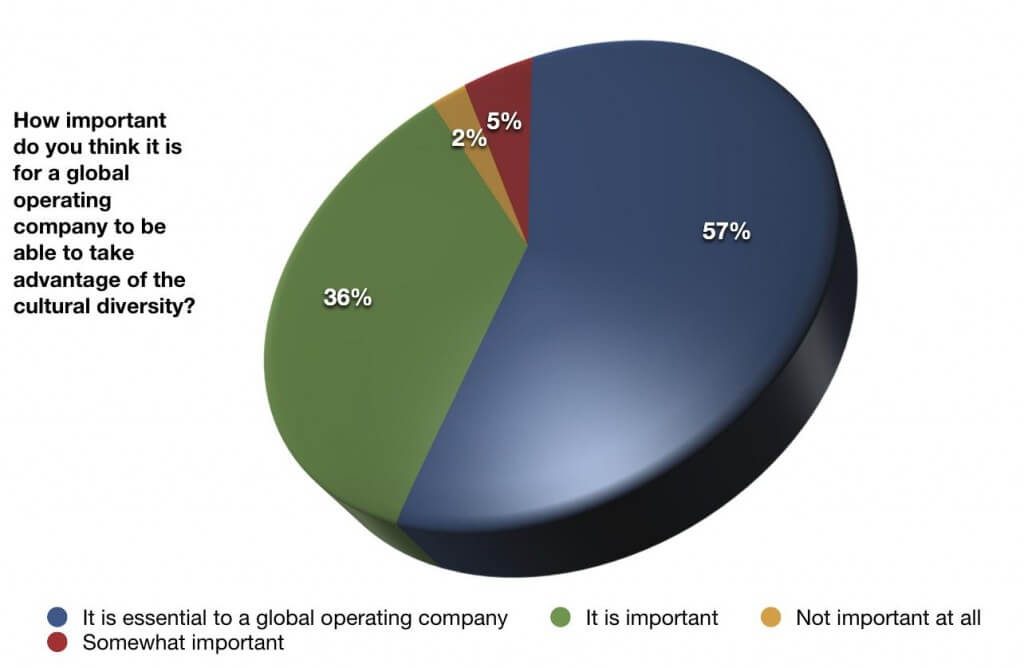

How important do you think it is for a global operating company to be able to take advantage of the cultural diversity?

As I pointed out in the beginning the discipline of taking advantage of the cultural diversity in the workplace is a blind spot to many managers even in large global operating companies. Many managers still manage their organisation the same way they did 10 years ago despite a lot of changes have happened in the external environment. More companies have become global primarily through mergers or acquisitions and the global competition has increased dramatically due to new technologies, de-regulation and emerging economies in particular the BRIC countries.

As it was one of the foundations for my dissertation it was therefore important for me to determine the level of awareness of the cross-cultural issues and opportunities global operating companies have.

I didn’t ask about to which degree the respondents companies worked with cross-cultural issues because almost all companies do. I was far more interested in getting to know whether the cultural diversity in the workplace was seen as an obstacle or an opportunity. The response surprised me a great deal. 93% of the respondents think it is essential or important that their company take advantage of the cultural diversity in the workplace. This can of course be done in many different ways, but it is definitely a showdown with the old attitude that we have seen in “old” global operating companies that there is only one way to do things – usually the way dictated by the headquarter.

The 93% in favour of a cultural reconciliation is also a clear sign that the respondents want a democratic or at least an open-minded leadership style that embraces the cultural differences in a way that makes sure that everybody is heard.

What is the ideal way of dealing with cultural diversity in the workplace?

The majority of the respondent meant that dealing with cultural diversity was either essential or important. The next natural step is to find out what they think is the best way to do it. As I described in my dissertation an organisation has a lot of workplace subcultures and it can choose to manage these subcultures in a number of different ways. They range from very controlled and hierarchical to loosely coupled entities with a great deal of autonomy.

The majority of the respondents (71 %) opt for an organisational model where there has to be some common norms and values, but with room for the cultural diversity to flourish. The 10 million ! question is of course: How do we do that? In my dissertation I answer that question based on previous client cases and with reference to the theories about how we reconcile cultural differences and the theories about subcultures. A lot of innovation power has been put into developing a new model for organising, motivating and rewarding people in global operating companies. These new findings will be implemented in Gugin’s service offerings to our client’s worldwide.

Like in the previous question I am surprised that so many respondents acknowledge the importance of protecting the minorities in the bigger society (company). It relates directly to the theories about how we accord status. I covered these theories in the dissertation. The second most popular option was to give as much freedom to the different workplace cultures because this is the only way that they will perform to their maximum. This is how conglomerates work. I doubt this option is ideal for companies who have one or few related products to sell in many countries. Only 7% thinks that there has to be one way of doing things and you as an employee can either take it or leave it. I expected this number to be higher because it is often an attitude I hear as a consultant when I work with companies who are in doubt of how they shall face the challenges of the globalisation. Maybe they are just frustrated because they don’t know what to do in that situation.

The answers to this question also tell me that it will be important that we in Gugin deliver a model for reconciling the dilemma of on one hand having a global organisation where you want economies of scale and on the other you want to be close to you customers and employees globally. That can only be achieved through local customisation of products and policies.

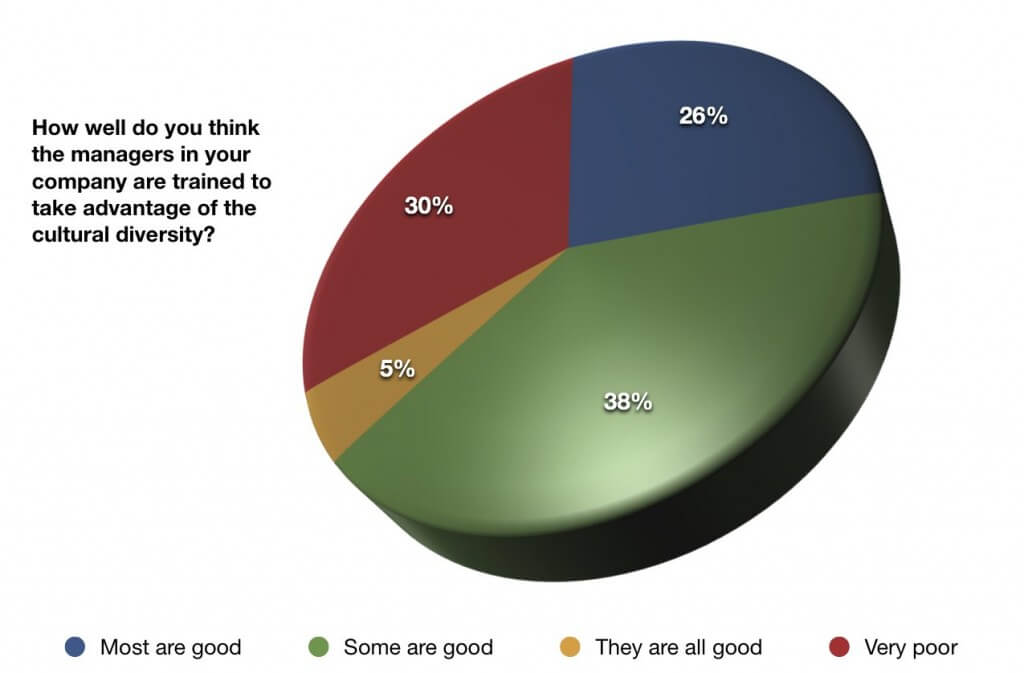

How well do you think the managers in your company are trained to take advantage of the cultural diversity in the workplace?

At this point we have determined that the respondents find that it is very important or essential for global operating companies that they know how to deal with cultural diversity in the workplace. We also know that the majority of the respondents opt for a model where the corporate culture leaves good room for the cultural diversity to flourish.

The next question is: How well equipped are our managers for this new complex task? It doesn’t help a lot if the senior management of a company decides on a way to take advantage of the cultural diversity in the workplace if the managers further down in the organisation don’t know how to carry it out.

As you can see from the responses we have three blocks of almost equal size. 38% believe that some of their managers are good, 30% believe they are very poor and 26% believe that most managers are trained well to deal with cultural diversity. With that deviation I think it is fair to assume that 50% of the managers need training in order to be capable of dealing with the cultural diversity in a way that it becomes an advantage for the company. I did expect that number to be higher based on the answers to the previous questions. As far as I can see from the answers there is no company who stand out as having particular good or bad managers. All the answers seem to be fairly evenly spread.

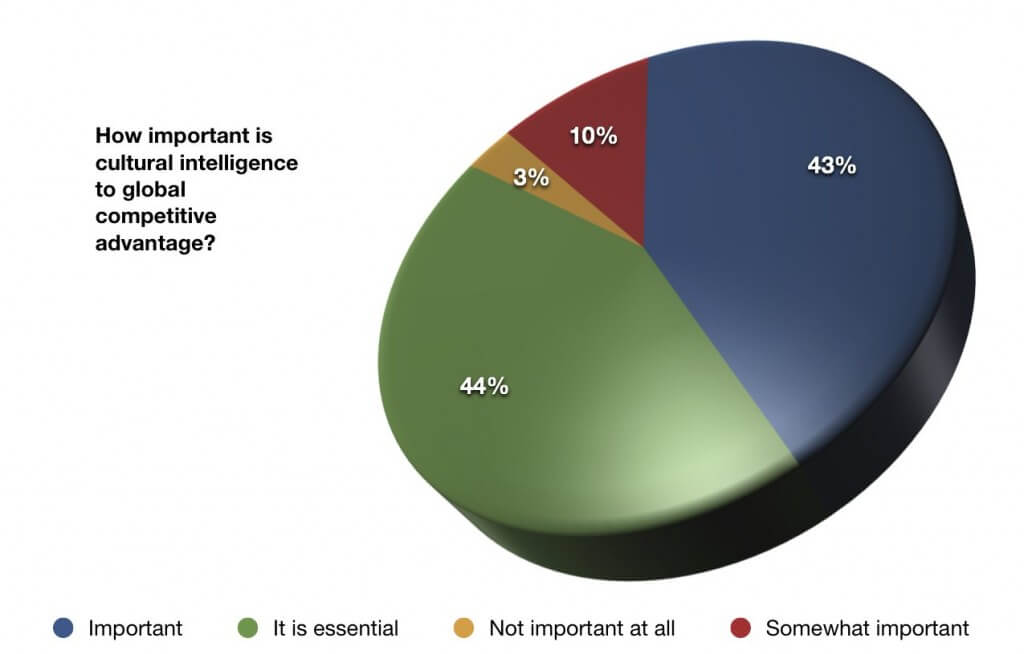

How important is cultural intelligence to global competitive advantage?

Cultural intelligence is a term I developed a lot in my dissertation. It refers to the skills you have as a manager that enable you to see beyond the artefacts of another person and understand, accept and embrace that persons values and norms on his or hers premises.

This is not an easy task. I have done hundreds of courses and coached numerous executives on this. In my dissertation I used Edgar Schein’s 3-layer model as a foundation for explaining and developing cultural intelligence. And based on the answers here it seems to be a very important topic for clarification and discussion. 87% of the respondents think that it is essential or important to possess cultural intelligence as a manager because it is skills that enable your company to take advantage of the cultural diversity. Not only do the results show me it is an important topic for my dissertation, it should also rank high on the companies training programs. In Gugin we have worked with this for over 10 years, developing solutions and implementing them in the companies we have been working with and it pays off for our clients.

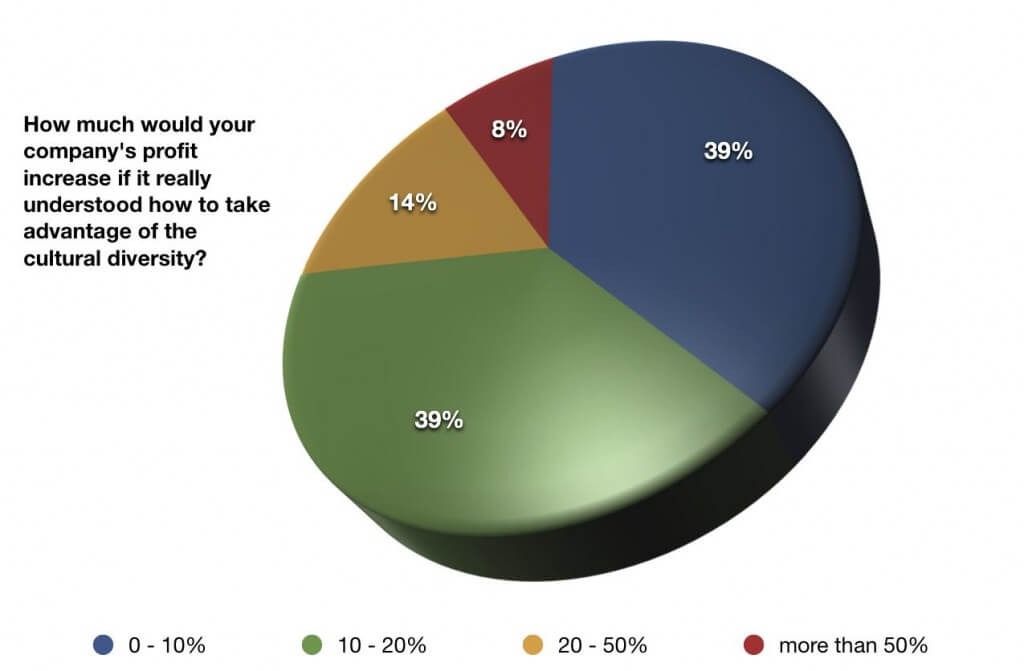

How much would your company’s profit increase if it really understood how to take advantage of the cultural diversity in the workplace?

This question is of course hypothetical since you will never get to know the result even if a company really managed to take advantage of the cultural diversity. The question is presented in a way that it leaves a lot of room for the respondent to interpret “take advantage of cultural diversity”. I did that deliberately even though I have had a couple of statisticians on my back for doing it. There are thousands of ways a company can take advantage of the cultural diversity, and I wanted to lead the thoughts of the respondent to the relevant ways for him or her.

By linking the cultural diversity to profit the respondent will think about situations where he or she has been involved in incidents where they either have succeeded or failed because of the cultural diversity. They will think about situations where they won a new client because they managed to have an international team working together in the sales process, or the respondent will think about situations where they have failed on delivering because of cultural frictions and internal fights that can be rooted back to cultural differences. All these incidents have a financial impact either positive or negative, and it is my belief that the cost of not being able to take advantage is represented in the chart above.

39% find that they can only improve the profit with 0 – 10%. Another 39% believe that their company could improve its profit with 10 – 20%, while 14% believe that profit could be improved with up to 50% if the company knew how to handle cultural diversity well.

If the managers who have answered the questions are true and honest in their feelings about how much their company could increase profits then a lot of companies have a large hidden potential. And according to one of the previous questions 50% of the managers are not well equipped for possessing a management position in a global operating company.

Think about what could happen if a company had the courage, skills and knowledge to release the power of cultural diversity? Not only would its profit increase, people would feel more motivated and produce more for less money.

To which degree do you feel motivated by the incentives your company is providing?

In my I have a section dedicated to motivation and reward. It is a topic that has interested me a lot – especially in relationship with cross-cultural management. Depending on our culture we feel motivated by different things, so motivation- and reward systems are definitely key areas to adjust to local cultures if a company wants to motivate and reward its people in the best possible way at the lowest overall cost.

With this question it is my intention to determine to which degree people feel motivated by the incentives the companies are offering through their workplace culture. There is a clear link to cross-cultural management in this question due to the fact that we feel motivated by different things depending on among other factors, cultural background. I covered that in more details in my dissertation and it is also an area I have been working with in Gugin continuously over the years.

25% of the respondents do not feel motivated at all or just a little by the incentives the company is offering. Think about it – it means that 25% of the bonuses, salary increases; company cars etc. have absolutely no positive impact on the results that the company produce. Another 40% of the respondents only feel motivated to some extend by the incentives.

In my dissertation I dealt in detail with how motivation works and the linkages between de-motivation and motivation factors. If a global operating company only has one incentive program it will waste a lot of money because an incentive will only work as an incentive in the culture where it is originated. So what serves as a motivation factor in one culture can easily serve as a de-motivation factor in another culture. Example: Some cultures have a preference for individual reward. If you try to reward individuals in

cultures where there is a preference for group rewards the reward will serve as a de- motivation factor because the individuals in the group will do almost anything not to receive the reward. Because if they do they will feel they have betrayed their group.

cultures where there is a preference for group rewards the reward will serve as a de- motivation factor because the individuals in the group will do almost anything not to receive the reward. Because if they do they will feel they have betrayed their group.

How much would your company’s profit increase if all employees were motivated and rewarded with respect to their cultural norms and values?

Summarisation and conclusion of the survey

The survey has shown that there is a great awareness about the importance of cultural diversity. It is acknowledged that it is essential or important for today’s global operating companies that they are able to turn the potential cultural friction into a source of synergy. In the survey it is also acknowledged that not only should the companies try to minimise the cultural friction; they should also try to gain competitive advantage from being a multi-cultural company. And since gaining competitive advantage from cultural diversity was the subject of my dissertation I was very pleased that it is an area of importance to most managers in global operating companies. It can also be concluded that these companies can gain a lot by becoming better at motivating and rewarding their employees around the world. One size doesn’t fit all. It might be easier to administer for the headquarter, but a uniform motivation and reward system can easily generate a lot of cultural friction when it is implemented outside the cultural zone of its origin. In my dissertation I proposed a new way of looking at motivation and reward including a fairly simple and practical example of how a new motivation- and reward system can be implemented that not only will give more satisfied employees but also save the companies for a lot of money.

Motivation has a lot to do with cross-cultural management as I have pointed out above. Not only do we feel motivated by different factors depending on where we are culturally it is also different factors de-motivating us.

De-motivation and motivation are closely linked. If we feel de-motivated by something it cannot be compensated with another motivation factor. If for instance we feel de- motivated by bad leadership or micro inequities then it can’t be compensated with a bonus, a company car or a pay raise.

That means that a company can easily be leading the salary game in an industry and still have very de-motivated employees and managers.

This question deals with how much more productive the managers could be if they were motivated according to their cultural preferences, that means their norms and values. Only 31% is in the lower 0 – 10%, meaning that nearly 70% of the respondents believe that their company’s profit could increase with more than 10% if they were motivated correctly. Nearly 30% feel that the profit could be improved with minimum 20% if they were motivated correctly.

This question relates to another topic I covered in detail in my dissertation, namely cultural friction. It is the friction that occurs when a corporate culture suppresses the

cultural norms and values of the people working with the company. When we feel our norms and values compromised we feel de-motivated and inevitably become less productive. The chart above indicates that there is significant cultural friction in almost 2/3 of companies participating in this survey.